Food, Feed, and Failure: The Shortcomings of the Food Industry

Michael Banks- June 6, 2016 Foodborne illnesses pose perhaps the greatest immediate threat to the average consumer. It’s estimated that every year in the United States there are “76 million illnesses, 325,000 hospitalizations, and 5,000 deaths” all due to foodborne disease. Marion Nestle, Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at New York University, even comments in her book, Resisting Food Safety, on how “such numbers undoubtedly underestimate the extent of the problem”. With astounding numbers such as these one might think that everything humanly possible is being done to prevent foodborne illness. Unfortunately, this isn’t true, and that responsibility has been thrust upon us, the consumer.

Foodborne illnesses pose perhaps the greatest immediate threat to the average consumer. It’s estimated that every year in the United States there are “76 million illnesses, 325,000 hospitalizations, and 5,000 deaths” all due to foodborne disease. Marion Nestle, Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at New York University, even comments in her book, Resisting Food Safety, on how “such numbers undoubtedly underestimate the extent of the problem”. With astounding numbers such as these one might think that everything humanly possible is being done to prevent foodborne illness. Unfortunately, this isn’t true, and that responsibility has been thrust upon us, the consumer.

There is a multitude of government agencies assigned to protect food industry consumers such as the FDA and USDA, but an overall lack of organization and concern for consumer health has put us at risk. The consumer has been at the mercy of industrialized food for nearly a century and it is worse now than ever. It is up to the consumer to enact change and revolutionize the food industry.

Let’s start at the beginning. The root of the problem are foodborne illnesses themselves, so what are these illnesses and where do they come from?

Odds are the average consumer has heard of at least 1 foodborne illness. Some of the most common foodborne illnesses include Salmonella and E.coli, with Mad Cow Disease also being a serious threat. Not all foodborne illnesses are the same however. For example, contracting E.coli can lead to death while salmonella will likely make you experience stomach pains. In addition, Salmonella can cause arthritis, a far step from stomach pains, but thankfully it takes thousands of salmonella microbes in order for it to take hold in someone. Mad Cow Disease often remains among cows, but on occasion humans can contract a special form of it, which is fatal. People usually don’t think twice about what could be in their food, or figure that if there is something in what they’re eating then all they will experience are some slight pains. What many don’t realize and what they should be clearly made aware of are exactly what risks they’re taking when they take a bite of their favorite food.

Perhaps the most dangerous foodborne illness that we face currently is a specific strain of E.coli, strain O157-H7. This strain has been known to be especially deadly and is more common than Mad Cow Disease, making it a top contender for first place in a list of foodborne illnesses you really don’t want to get. Like salmonella, E.coli (including the strain O157-H7) is a bacteria which works its way into our bodies by infecting the food we eat. Nestle explains what makes O157-H7 so dangerous.

“…at some point, it picked up a Shigella gene for a toxin that destroys red blood cells and induces a syndrome of bloody diarrhea, kidney failure, and death. This toxin is especially damaging to young children” (Pg.41)

Much to our misfortune, Nestle is telling the truth. Barbara Kowalcyk, current foodborne illness prevention advocate, lost her 2 ½ year old son Kevin suddenly to E.coli O157-H7 after he ate a cooked hamburger infected with the strain. In Food Inc. we see home videos of the family vacation Kevin and his family were on. They were having fun, playing on the beach and laughing, most likely looking forward to having a family meal together later that day. They weren’t worried about whether or not their food was going to kill them, and they shouldn’t have to. Much like the Kowalyck family most likely believed, most of the population might think that simply cooking the hamburger would kill any bacteria or viruses infecting meat. However, O157-H7 is extremely resilient, adding to its tenacity. Tragically, the Kowalyck family found this out the hard way. O157-H7 “resists heat…resists drying, can survive short exposure to acid and sometimes resists radiation and antibiotics”. Perhaps most concerning is the fact that is takes as little as fifty O517-H7 microbes to induce symptoms, noted by Nestle as “a minuscule number in bacterial terms”.

The most effective method to stopping the flow of anything is at the source. No infected animals means no infected meat which in turn means no infected consumers, so where is the source? In this case, the source is where the animals are raised and fed, feedlots.

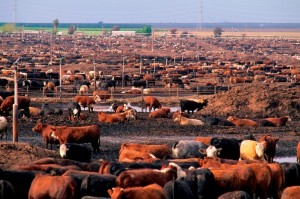

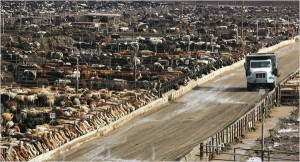

Feedlots can be anything from enormous plots of land where thousands of cattle are held to long ‘houses’ filled to capacity with chickens or pigs. In either case, the conditions are prime for infestation. While in these feedlots, animals are forced to remain in very close proximity to each other, almost tripping over one another. Due to there being little to no space to move, animals are forced to stand in both their own and other animals’ manure for nearly the entirety of the time they spend in these feedlots. Respected food politics expert Michael Pollan, author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, explains in the Emmy winning documentary Food Inc. what this means in simple terms, “Manure gets in meat”. As it turns out, E.coli O157-H7 is transferred through feces, meaning that one infected animal can infect multitudes of other animals.

As an example of how easy this makes it for consumers to come in contact with infected meat, consider this. “Americans consume 200 pounds of meat per year/per person”, and according to health officials, “…just one infected beef carcass is sufficient to contaminate 8 tons of ground beef”! It isn’t even necessary to consume meat that’s tainted with E.coli, all it takes is contact, direct or indirect, with infected feces. It could be as simple as shaking the hand of “infected people who shed it in their feces and pass it along from unwashed hands. This makes it very important that consumers cook their meat as thoroughly as they can and that they wash their hands regularly, especially after handling meat.

Some however, such as strong industrial farming advocate Blake Hurst, directly contrast Pollan on many points. One such contrast is Hurst’s opinion that keeping animals caged is in fact the better option. Hurst himself is an industrial farmer out of Missouri and the President of the Board of Directors for the Missouri Farm Bureau. He argues that free range animals such as chickens and pigs will “increase the price of food, using more energy and water to produce the extra grain required for the same amount of meat” (Pg. 5). He may well be right, the price of food may increase, but so will our safety. Don’t you think that Kevin’s family would pay any amount of money if only the food he was eating would’ve been safe? If anything, Hurst’s reasoning simply helps to expose that industrial farming is all about getting it done cheaper and faster. In an interview with Frontline, Michael Pollan Discusses feedlots further. He recounts a personal experience he had in which he visited feedlots in Kansas. Pollan sums up his opinion of the feedlot, calling them in general “medieval cities… because they are cities in the days before modern sanitation”.

What makes matters worse is that the feed industrial farmers are feeding their cattle increases E.coli found in cows. In today’s industrial farming world, cattle are fed a primarily corn based diet. In fact, corn, in conjunction with soybeans, makes up 70% to 90% of most commercial animal feed. In Food Inc. an expert points out that if grass is fed to cattle for just a few days, replacing the corn heavy diet, then the cattle will shed 80% of E.coli in their gut. Farmers feed these foods to their cattle in order rapidly increase the growth of the animal in question, in this case cattle. The name of the game in today’s food industry is to turn out as much as you can as fast as you can for as cheap as you can do it.

The situation is indeed dire, but not only because foodborne illnesses are such a great threat. What makes this predicament even more dangerous is the lack of government action when it comes to protecting the consumer. In the government’s defense however, the system has become extremely complicated, even though it has been of their own doing. In today’s system, there are 12 different government agencies housed in six separate cabinet-level departments. The most recognizable agencies of the group are perhaps the FDA, or Food and Drug Administration, and the USDA, or the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Even just between these two agencies nothing is simple. For example, the USDA regulates pizza with meat toppings while the FDA regulates cheese pizza. That means that if you get a half pepperoni half cheese pizza you are involving at least two government agencies in your meal. This illustrates how even the simplest of things become more complicated with the ‘system’ that’s been put in place.

Where the real issues take place however are in the detection and resolution of food related issues. Earlier I offered some statistics on the number of hospitalizations, illnesses, and deaths related to foodborne illnesses. Those numbers seemed astronomical, but as astronomical as they were they are likely underestimated. This is because both the USDA and FDA are tasked with too much under demanding conditions. In Marion Nestle’s Resisting Food Safety, she explains this subject in detail. For example, the USDA, every year, must inspect

“animals at 6,000 meat, poultry, and egg establishments-and 130 importers- that slaughter and process 89 million pigs, 37 million cattle, and 7 billion chickens and turkeys, not to mention 25 billion pounds of beef and 7 billion pounds of ground beef”.

In order to complete the overly demanding task of inspecting all this meat they must have countless inspectors right? Well, maybe if 7,000 inspectors is considered a countless amount. However, having 7,000 inspectors is a godsend compared to the 700 employed by the FDA. The USDA is only responsible for 20% of the food supply too, leaving the FDA with more than they could possibly handle, especially with their “minuscule” $283 million budget, which really is minuscule by government standards.

As is evident, there is a lot of room for error with regard to government inspections of food, which causes estimates of foodborne illnesses to be horrifyingly shortcoming. This may be part of the reason why these agencies are also often negligent.

Perhaps most troubling is Marion Nestle’s recounting of her observations of the FDA while working as a member of the Food Advisory Committee there for 6 years. She noticed that the FDA had an “apparent perception of food issues as troublesome and unscientific rather than as challenging problems demanding a high priority and focused attention”, and that

“they often appear to be more concerned about their own turf-or that of the industries they regulate-than about protecting the health of consumers”.

This brings us to unsavory topic of corruption. In Food Inc. investigative journalist Eric Schlossor discusses how “Regulatory agencies are being controlled by the companies they are supposed to be scrutinizing”. We also see how individuals in high government positions, including positions in agencies such as the FDA, are on boards of directors for some of the 4 big beef processing companies. This would definitely explain why it seems as though the government just isn’t as invested as it should be with consumer health. It would also explain why back in 2002 the FDA, after 4 years, still had not “acted promptly” in enforcing a feed ban that prevented cattle from consuming tainted feed that would make them sick. It is this kind of routine lax behavior that is forcing us to take matters into our own hands.

We, as consumers, must make a conscious effort to enact change in the food industry. This can be accomplished by purchasing not food produced by the industry that has a revolting disregard for our own health, but from sustainable farms that produce wholesome food. Farms such as that of Joel Salatin, who believes in producing foods based on Mother Nature and who correctly points out that we have “lost integrity and accountability of all food”. By doing so, we will show both the corporations and government that we are done buying into their deceit, leaving them no choice but to change their ways. It’s time to take back our food.