The average salary of a Division I men’s football coach is $1.64 million, and $1.5 million for their counterpart, men’s basketball coaches whose team makes it to the NCAA tournament. Yet, the NCAA a “non-profit” organization had an annual revenue just shy of $1 billion in 2014 according to USA today, with 90 percent coming from March madness alone. With major college sports generating this type revenue year-in and year-out it’s difficult to grasp where all of this money is truly going, and why hasn’t it been returned to the stars of the show, the athletes. A majority of people may be unaware of the reality of this grueling business and its corruption. Throughout this piece I would like to bring forth the issues behind the scenes and discuss the potential, but controversial, topic of paying college athletes. Although division I college athletes are legally amateurs by the NCAA rules, they are acting as full-time employees to the university and generating millions in revenue of which they are not seeing a penny of. In the big picture, scholarships are not adequate compensation for the revenue being produced, and therefor college athletes should receive stipends beyond their scholarships.

Discrepancies among the NCAA

With an annual revenue of $912.3 million in 2015, the NCAA is considered a 501(c) (3) organization. Meaning that they are tax exempt under the IRS, and are pooled among other organizations such as Red Cross and the Salvation Army. But, in economic terms, the NCAA would qualify as a monopsony. This means that they are one buyer within a market of unlimited sellers, and in this case the sellers being the athletes selling themselves to colleges and receiving zero for their labor. The organization has made it clear that they will not condone the paying of college athletes that they consider to be “amateurs.” The term amateurism is expressed on NCAA.org and described as being the “bedrock principle of college athletics,” and “being crucial to preserving an academic environment in which acquiring a quality education is the first priority.”

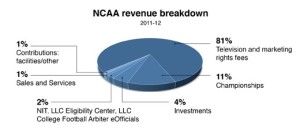

In 2012 the NCAA signed a 14-year agreement with CBS and Turner Broadcasting System for the rights to March Madness worth $10.8 million. In 2016 this contract was extended to 2032 in another $8.8 million deal. $1.5 million is the cost for a 30-second advertisement spot during the tournament. (Read more about revenue breakdown)

The underlying statement being made here is that these are “student-athletes,” with an emphasis on the student. However, graduation rates may tell a different story. There are two measures to ensure that an athletes earn a degree. First the U.S. Department of Education’s Federal Graduation Rate, and second the NCAA’s Graduation Success Rate. According to the NCAA, 100 percent of the members of the Duke men’s basketball team who entered as freshman in 2007 graduated. But, the federal measurement, which takes into account the percentage of full-time college student-athletes who enter as freshmen and finish with a specific degree within six years, calculated that only 67 percent of male players during that time period actually graduated. There is a large discrepancy among these numbers that may be due to the NCAA failing to take into account the “one-and-done” players, career ending injuries, or even drop outs. As long as these players were in good academic standings before their departures, they are also added to the positive graduation rates.

Where is all the money going?

Coach Krzyzewski, head coach of the Duke men’s basketball made a whopping $7,233,967 last year, along with another $5,400,000 made by John Calipari, Kentucky men’s basketball coach. Clemson University have written plans to build a $55 million complex solely for men’s football that includes sand volleyball courts, laser tag, movie theatre, barber shop and other amenities. Combined 48 of the schools from the wealthiest conferences spent $772 million on all athletic facilities. But, according to CBS News, only 3 percent of men’s basketball programs turned a profit last year. This may be due in part to cost pressure from the top schools to pay the coaches extremely high wages. Also, a report released by Delta Cost Project found that Division I universities on average spend about three to six time as much per athlete than they do on academics per student. Reminder, the NCAA’s main opposition to paying athletes is that they are “students first.” It’s hard to believe that these college athletes aren’t considered full-time employees that putting in over 40 hours of work just related to their sport each are students-first. After practice, film reviews, and scheduled lifting the players can finally get to their schoolwork. Such high demands of being an athlete have recently been linked to pooling athletes’ into general majors together. Evidence shows that the majority of college athletes have chosen a major in general studies. This due to a lack of ability to maintain the balance between their sport demands and school, or even because the coach told them to in order ensure eligibility. What does this say about the universities and the employees (coaches) who are supposed to be looking out for the best interests of the student-athletes? This situation has been corrupted and solely geared towards maintaining eligibility for top players in order to win games, rather than planning and pursuing a career for the future. The matter of fact is that college athletes being exploited for their work, or in this case their athletic performance while continuously turning nearly $1 billion into a yearly loss by wastefully spending money on extreme facilities that are exclusively geared towards athletic benefits and not academics. The NCAA and institutions pride themselves on the notion of having the best interest of the student-athletes in mind, but I’m not so sure this is the reality.

Reality of Full-rides

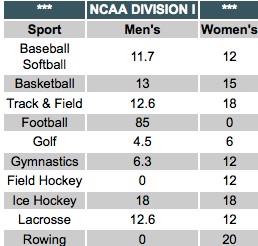

Not only is the money being generated by college sports an at-large issue, but the cost of being a full-time student-athlete on a full scholarship is often misleading. People often assume that there is a surplus of full-scholarships, or that scholarships are more than enough to “hand out.” However, the average amount of money awarded to division I athletes was $13,821 for men and $14,660 for women. Also just about 3 percent of all high school athletes will receive a complete full ride to play in college. There are also strict rules that have been put in place by the NCAA that establishes how many scholarships each team at a university can receive. Only six sports, commonly referred to as “head-count” sports, which include football, men’s and women’s basketball, women’s gymnastics, volleyball and tennis, have enough full-scholarships to cover the team in its entirety. On the other hand the rest of the collegiate sports teams are limited by the NCAA as to how many full rides that they receive.

This is the breakdown of full-scholarships per team allotted to the non-head count sports by the NCAA

Yet, this organization has an annual profit of about $145 million and is only returning about $12.3 in expenses for scholarships to the universities. This could be the biggest discrepancy for the NCAA and one of the main reasons that player’s unions and other people are demanding reform. In the 2011-2012 fiscal year, a study was conducted by Ithaca College researchers that reported the average expenses that a college athlete was required to pay beyond their scholarships was about $4,000. “Free rides” fail to cover the cost of living for a typical college student, but these athletes are still students before anything. Cell phone bills, gas money, groceries and rent for housing off campus are just a few of the additional expenses that a college student may see. These expenses may be taken care of if the players were able to have a part-time job, but once again the NCAA bans in-season work. Often it can even be difficult for athletes to find the time or money to get in three meals a day with their schedules. Recently University of Connecticut basketball start Shabazz Napier spoke out about this issue and stated, “there are hungry nights that I go to bed starving.” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fFdRk2DYolM)

Opportunity for Reform

The NCAA has a significant issue that must be attended to within the near future. With the multimillion dollar enterprise claiming itself as a non-profit organization through the IRS, it has come to a point of college athletic exploitation. The organization continues to fight off any efforts to find more money to pay student-athletes directly through stipends, but also wishes to leave the gap between their profits and the limited number of scholarships allotted to the non-head count sports. Also, they are holding onto their belief that these athletes remain students-first, when there is an abundance of evidence that points directly to men’s basketball and football simply being farm systems for the professionals to pick from. It seems that there needs to be a re-evaluation as to how much money is being spent on facilities and coaching, and more time spent of finding ways to bring the money back directly to the athletes themselves. After all, these college athletes are indeed the money-makers.

References

Deford, Frank. “Deford: Paying College Athletes Would Level The Playing Field.” NPR. NPR, 2 Apr. 2014. Web. 5 Apr. 2016. <http://www.npr.org/2014/04/02/297898279/deford-paying-college-athletes-would-level-the-playing-field>.

“NCAA.org – The Official Site of the NCAA.” NCAA.org – The Official Site of the NCAA. NCAA, n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2016. <https://www.ncaa.org/>.

Nocera, Joe. “Let’s Start Paying College Athletes.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 31 Dec. 2011. Web. 21 Apr. 2016. <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/01/magazine/lets-start-paying-college-athletes.html>.

Sanderson, Allen R. and John J. Siegfried. 2015. “The Case for Paying College Athletes.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(1):115-38.

Strachan, Maxwell. “NCAA Schools Can Absolutely Afford To Pay College Athletes, Economists Say.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 27 Mar. 2015. Web. 12 Apr. 2016. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/03/27/ncaa-pay-student-athletes_n_6940836.html>.

Zirin, Dave. “An Economist Explains Why College Athletes Should Be Paid.” The Nation. The Nation, 27 Mar. 2015. Web. 18 Apr. 2016. <http://www.thenation.com/article/economist-explains-why-college-athletes-should-be-paid/>.

What i do not realize is in reality how you are now not actually a

lot more neatly-favored than you might be now. You are so intelligent.

You recognize therefore considerably relating

to this subject, produced me in my view consider

it from so many numerous angles. Its like men and women don’t

seem to be fascinated unless it is one thing to accomplish with Lady gaga!

Your personal stuffs outstanding. Always take care of it up!