Streaming music services are killing the music industry. It may be more slowly than what file sharing services like Napster were doing 15 years ago, but just ask the artists; while they might be getting paid, it’s a pittance compared to real record sales.

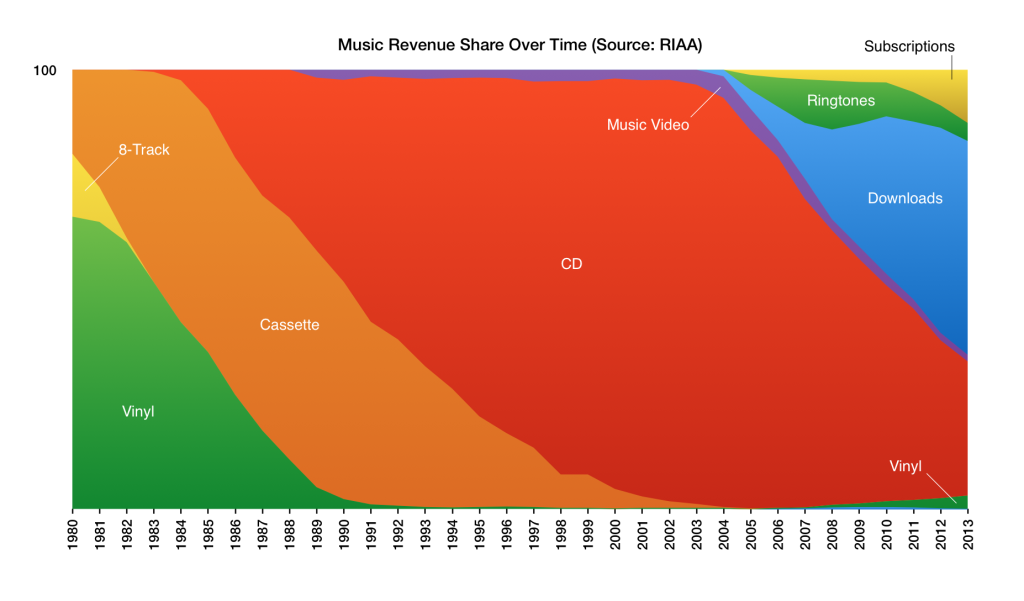

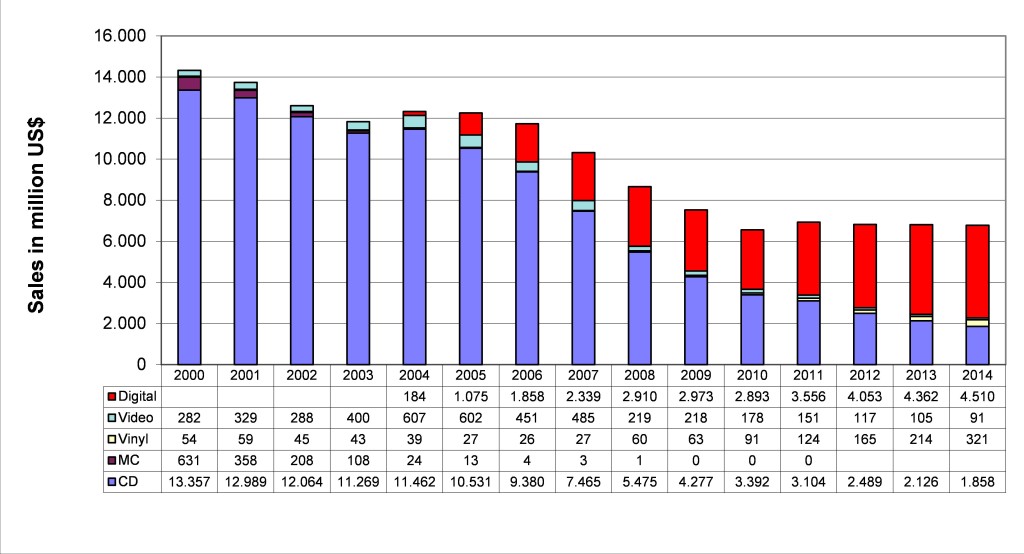

It’s no secret that the music industry has changed a great deal since the early days of AM radio and Edison cylinders, but the last two decades have brought about some of the largest changes in the way that music is distributed and consumed as compared to any other. Most importantly, physical media sales have taken a nosedive, with CDs making up about 30% of the market that the format used to dominate.

Thanks to file-sharing, peer-to-peer services, like Napster, that came about in the early 2000s, consumers have come to expect cheaper (read: free) ways of acquiring the music they so desperately desire.

We can’t blame it all on Napster. The iPod, MP3 players, and growing hard drives all begged to be filled with files, and the internet has been happy to oblige.

Peer-to-peer software like Napster, Kazaa, Limewire and perhaps a dozen others all made one thing clear: people believed music was no longer worth paying for.

At a time when a compact disc was upwards of $15.99, file sharing allowed listeners to pick and choose what they downloaded at a reduced cost.

Now the world’s largest music marketplace, iTunes also pushed this new paradigm, virtually ending the era of buying albums when it pushed record distributors to allow users to download individual tracks, instead of the whole record.

This fundamental change cannot be understated: by breaking the album down piecemeal into individual songs, artists and labels were guaranteed a much smaller revenue than if the whole album had to be purchased.

Because of antiquated laws that could really only be enforced on terrestrial AM/FM radio stations and in physical stores, Apple and others were able to guarantee only a small portion of revenue to labels and artists.

Testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Downloading Music on the Internet back in July of 2011, Lars Ulrich, founding drummer of metal band Metallica, said, “With Napster, every song by every artist is available for download at no cost. And, of course, with no payment to the artist, the songwriter, or the copyright-holder. If you are not fortunate enough to own a computer, there is only one way to assemble a music collection the equivalent of a Napster user, theft.”

A stinging review of the service for certain, and it brought plenty of backlash from fans and non-fans of the classic thrash metal act. Many fans professed their love for the artists that they downloaded on Napster, but said that when it came down to it, they felt they had spent enough on prior ticket, CD, and merch sales to warrant the free downloads.

Piracy will probably never truly die, but as various piracy software’s and services came and went, other changes in music distribution occurred after Napster ultimately ceased in 2001.

Technology is constantly advancing, and as flip phones gave way to smartphones and Wi-Fi spread into public spaces, it was only a matter of time before a new way of accessing music came about.

Enter streaming music services. In 2011, streaming radio service Pandora began offering users a personalized, customizable way of hearing some of their favorite music, on-demand, all for free. You can choose an artist, song, or genre and Pandora will use your preferences to create a streaming playlist, but unlike making one yourself in iTunes, you can’t control what songs comes next. You simply hit a ‘thumbs up’ or ‘thumbs down’ button and Pandora’s software determines what to play next.

Free is definitely the biggest part of Pandora’s appeal. Users that do not pay for a subscription must endure a short ad every few songs, or they can pay about $5 a month to remove the ads. This is what is considered a “freemium” model: users can access the service at no cost, but with ads that generate revenue for Pandora, or they can upgrade to the ‘premium’ service that guarantees no ads.

Writing in The Independent, a national newspaper based in London, music industry and business journalist Hazel Sheffield said, “Music has always been a portfolio business. Digital downloaded music, played on iPods and phones, was thought to be the next big thing, but it is already in decline. In 37 global markets, including South Korea, Sweden and Mexico, streaming now generates more revenue than downloads.

As Sheffield points out, streaming has overtaken downloads in popularity. The juggernaut responsible for such a hostile takeover?

Spotify.

While Spotify had been around in Sweden and the rest of Europe since 2008, it took them several years and a lot of negotiating, along with several million dollars, to get American record labels on board so that they could launch their service in the US to any guaranteed success.

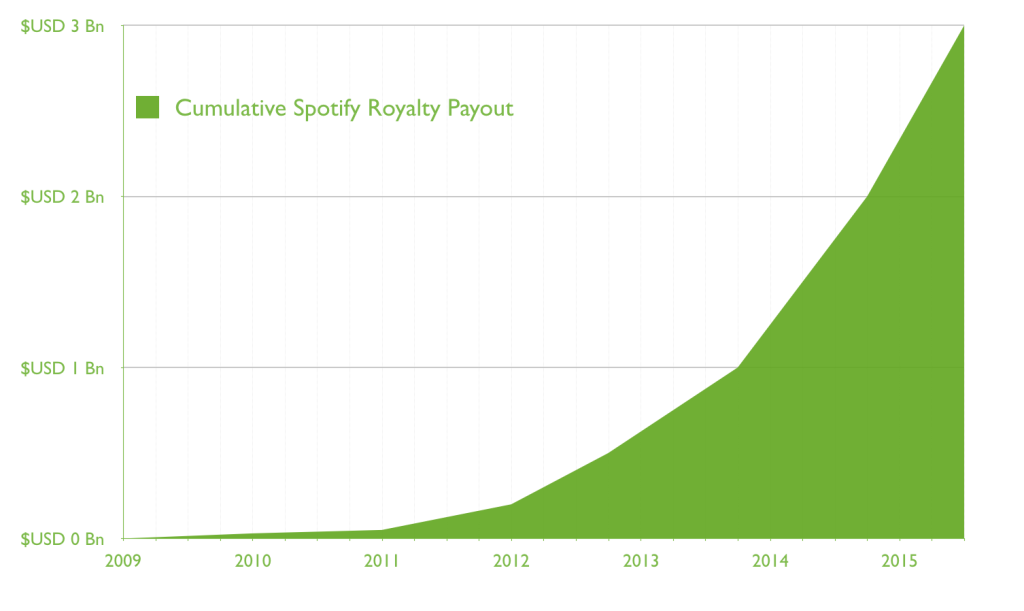

But succeed is just what Spotify did. According to their own website www.spotifyartists.com/spotify-explained, they are generating upwards of $3 billion dollars in royalties for the music industry, from a combined 75 million users in 58 markets worldwide.

Much like Pandora, Spotify is a freemium service. You can select an artist, their discography, or their album, hit play and listen to entire albums or catalogs on shuffle, with an ad after every third or fourth song.

For $9.99 a month you get access to Spotify Premium, which removes ads, removes skip restrictions, and even allows users to save songs or albums for listening when they go offline.

One might think that $3,000,000,000 is a lot of money, and while it certainly is, it’s not like that money goes straight from Spotify right into the hands of the artists.

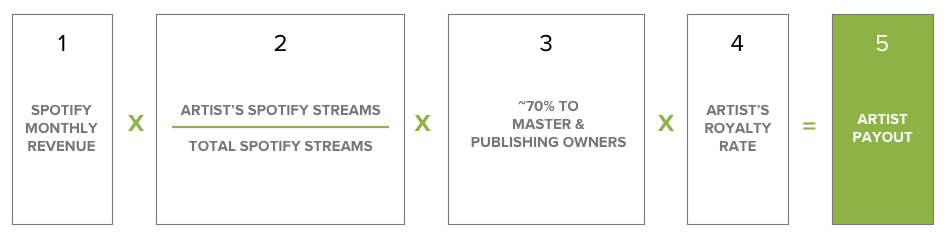

The chart lays it out in only relatively obscure terms: Spotify earns a monthly revenue, which is then multiplied by the fraction of an artists streams over Spotify’s total monthly streams. Then this amount is further divided, with 70% going to the copyright holders. Finally, each artist has negotiated a royalty rate.

Current estimates place the average revenue per stream at 0.7¢. NYU songwriting professor Mike Errico clarifies in an article in The Independent that, “Spotify, the clear leader in the streaming space, pays after 30 seconds.” That means if your song is either under 30 seconds, or a user skips it before they hit the 30-second mark, the artist doesn’t get paid.

Artists have spoken out against the unfair pay scheme that Spotify employs, and other services mimic, in different ways. Worldwide pop superstar Taylor Swift famously placed an open letter to Spotify in the Wall Street Journal back in 2014 when she refused to allow her most recent album 1989 to be available to stream.

In the letter, Swift poignantly wrote “There are many (many) people who predict the downfall of music sales and the irrelevancy of the album as an economic entity. I am not one of them. In my opinion, the value of an album is, and will continue to be, based on the amount of heart and soul an artist has bled into a body of work, and the financial value that artists (and their labels) place on their music when it goes out into the marketplace. Piracy, file sharing and streaming have shrunk the numbers of paid album sales drastically, and every artist has handled this blow differently.”

Since then, she has embraced Apple Music and can even be seen in TV commercials for the streaming service.

Or take, for example, Adele. The singer-songwriter released 25 in November of last year and by years end had sold upwards of 8 million copies. The album was not and still is not available to stream.

Things get even trickier when you consider who must get paid before the artist gets their share. As Lars Ulrich had mentioned earlier, there’s a lot of people that make a recording possible, and now they’re relying on a cut of seven-tenths of a penny per 30-second or longer stream.

Kate Swanson, a grad student at Indiana University, summarized it nicely in an article in the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association Journal. “For sound recordings, artists receive a percentage of the wholesale price. Superstars can get 20 percent, but most get 12 percent to 14 percent. On a $10 CD, a musician or band could make $1.20 to $1.40. Divided evenly between four bandmates, that amounts to a grim 30 cents each. On a 99-cent download, a typical artist may earn 7 to 10 cents after deductions for the retailer, the record company, and the songwriter.”

The 70% that is shown going to master and publishing owners in the above chart is divvied up between performing rights organizations (PROs) and publishers. Each holds and protects a separate copyright: one for the recorded sound, and the other for the musical work (think of that as the actual notes and words on sheet music).

These laws have remained relatively unchanged since the 1980’s, long before even the CD was popular. Because of this, there is no set law on how much money a streaming service must pay out to a label or artist.

So the problem is clear: the legal arena hasn’t caught up with the cultural one. But the solution much murkier. Lawmakers, musicians, and industry pros are going to have to band together if they want to create the radical changes needed in music industry law to guarantee a fair royalty scheme for artists. Otherwise, artists will follow in the footsteps of Adele, Taylor Swift, and many others and attempt to get their fans to buy music once again.

1. My title, “Streaming Music: How Revenue Streams Are Trickling Out” is just about as thought provoking as I could come up and still keep things short. I believe it is informative enough without revealing the entire point of my article. The lede is short and to the point: streaming music is killing the music industry, albeit more slowly than piracy had been doing. It may not be the most clever lede, but it is very direct and leads the reader into my article.

2. I believe the introduction helps lead the reader through a modern history of why the music industry has been in decline. While I don’t get too much into streaming in the first few paragraphs, it places my controversy in a historical and temporal context, telling the reader how we got to where we are.

3. By placing my controversy in a temporal context, I provide plenty of support and a timely evolution of this problem. By providing the reader with a number of experts and external sources, and also tying the current problem of streaming music revenues with the same problems as discussed around the advent of piracy software, I show how things have really not changed and that the problem basically remains the same. Based on feedback to my unit 2 presentation, it would seem most of my classmates were not aware of this issue, so I feel like I’ve uncovered yet more that the average music fan would not be aware of.

4. By discussing the issue in a historical manner (from past to present) I believe I’ve kept my point clear. The presentation is unique that instead of tackling only the problem as it is today (low revenues from music streaming), I bring in some of what has lead up to the advent of music streaming. Most of the sources I used did not take into account the actions of Napster and others 15 years ago.

5. I feel that, by historicizing my topic, I have given the reader a straightforward, yet thought provoking piece. I am challenging the average music listener that may know little or nothing about the way that they procure music, and offering a younger generation background that they probably have only a surface level understanding of. I have kept everything in a temporal order that also helps outline the development of my main claim.

6. I’ve found a variety of sources from many different sorts of authors with different backgrounds that helps to illustrate how people across many fields are thinking about my topic of controversy. I bring their points together to form a cohesive argument that shows how important it is that the legal field catch up with modern technology so that the music industry might thrive once again.

7. I have several visual sources, primary research that delves into just what those graphs mean, and 6 secondary sources with 1 of them being a scholarly journal article.

8. The quotes I chose illustrate many points in ways that I could not say in any more certain terms. Lars Ulrich’s quote in front of the Senate committee is contextualized and conversed about in the piece, as are all of the other quotes I chose. No mic drops.

9. By taking quotes from those that people might not necessarily think of as sources of authority (Lars Ulrich, a drummer; and Taylor Swift, a singer), I provide insight into the controversy that shows that artists are fearful about more than just filling their own bank accounts. By showing that these musicians are also concerned about everyone else in the industry, from people at their level all the way down to engineers at studios, I feel that I can persuade many readers to dig deeper into the topic themselves and learn more about how the whole industry works.

10. The visuals I’ve chosen show very effectively how streaming and the digital age have effected the industry. By discussing them in the text directly, I use them in a meaningful way, and without them the reader would be left searching for said visual in the pages of the magazine.

11. My final draft was almost entirely different from the second draft, as by the second draft I had not yet decided how to incorporate many of my sources. Earlier drafts were more like the TED Talk… lots of background info but no incorporation of third parties that I allowed to speak for themselves.

12. I used a hyperlink for each new source I brought in, linking back to the original article or source. I believe the way I wrapped them around a sentence or section of a sentence and not just a sources name makes them stand out and gives the reader a better idea of what they are about to be linked to.

13. I edited on my own to the best of my ability. I found no major flaws in my writing, and always try to write as succinctly as possible. I kept most sentences short to avoid any run-on confusion. I believe my writing style to be appropriate for an NYT Magazine readership.