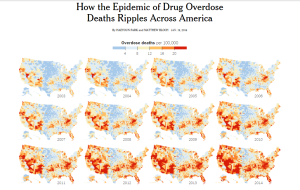

Image from the New York Times

Last October, Amy Pelow started a support group in Oswego, New York for the parents and loved ones of heroin addicts. Pelow discovered her 17-year-old son was addicted to heroin when she received a phone call informing her that he had overdosed and was currently being hospitalized. She rushed to the Oswego Hospital to find his lanky, teenage body hooked up to machines and injected with various tubes. Since then, he has overdosed 8 times and rotated in and out of rehabs and jail multiple times.

Pelow calls herself a reformed ambulance chaser.

When she used to hear ambulances howling across the small-city sprawl of Oswego, she would instantaneously text and call her son. If he did not respond immediately, she would hop into her car and track the sound of the mechanical wailing. The whole time she would image her son’s unconscious body waiting at the end of her chase. But after six years, she has retired from this hunt.

The prevalence of heroin throughout this country is an epidemic that has claimed headlines and lives with increased frequency in the past decade. Heroin-related deaths across the country jumped 39 percent from 2012-2013 and the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths nearly quadrupled from 2002 to 2013, according to the CDC.

In New York State alone, the number of deaths attributed to overdoses of opioids – which does include both heroin and prescription painkillers such as Oxycontin – rose from 940 in 2004 to 2,044 in 2012 – 117 percent jump, according to the state Health Department.

In downtown Syracuse, there is a needle exchange program called ACR Health. In 2011, they had just 16 people picking up clean needles. This year, they are already at 753.

Although the statistical and anecdotal evidence revealing the extent of the heroin epidemic is clear and straightforward, the factors that created and sustain this situation are more complex. The most widely accepted theory behind the heroin epidemic is one revolving around regulation oversight and greedy pharmaceutical companies, according to a commentary recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

About twenty-five years ago, pharmaceutical companies started pushing the over prescription of opiate pain killers, such as OxyContin and Vicodin, in order to increase their revenues. The intensity of these drugs and the generosity with which they were prescribed led to high rates of addiction over time. Grandmas and teens, the rich and the poor started getting hooked on these serious pain killers.

Eventually, physicians and authorities realized this incredible rate of addiction and the government subsequently started cracking down on this excess of opiate prescription. Means were implemented to limit and monitor the amount of opiates a doctor could prescribe per a patient and data bases were established that tallied the amount of opiates patients received from different doctors. Measures such as these successfully decreased the availability of and access to this very addictive drug.

But then, tens of thousands of people were suddenly looking for a similar high that would blunt their withdrawal symptoms that felt like hell. It was at this time that ingenious Mexican drug cartels took this opportunity to flood the market with heroin, another type of opiate. And there was quite a substantial consumer base waiting to be exploited.

Laura Samson’s* brother started with pills and now he battles a sometimes 100-dollar-a-day heroin addiction. “I remember the day I found out he was a heroin addict, “Laura wrote in a blog post, “My body shook, I grew nauseous, and for the first time in my entire life, my heart hurt. His life would now be a constant battle between happiness, addiction, and the law.”

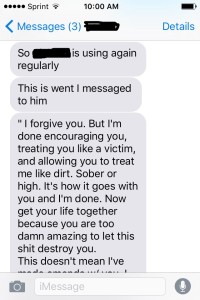

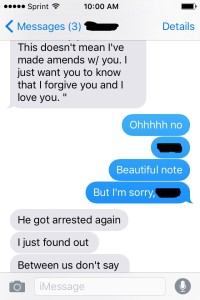

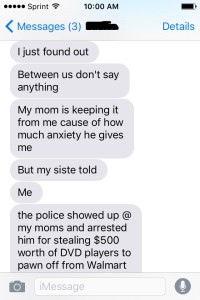

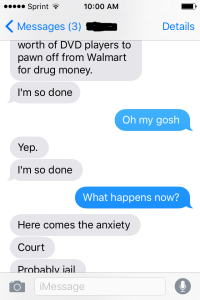

Laura’s story captures the heartache that more and more families and loved ones across that nation are experiencing as the number of heroin users creeps upwards. Their reality is a tortuous oscillation between insatiable fear for the life of the user and anger at the user for how they have reduced themselves and dragged all who love them into a terrify cycle of anxiety and hopelessness.

Images provided by author

In addition to the mental, emotional and physical turmoil that people addicted to heroin and their loved ones experience, another massive obstacle is defiantly placed between them and recovery: The overwhelming lack of resources.

Even if addicts want to quit, there is simply not enough room in rehabilitation centers nor enough effective rehabilitation practices and facilities. Some specialists in places like Central and Upstate New York offer intense, one-month rehabs. This way they are able to crank people in and out as there are so many addicts looking for help and not enough available services. But the relapse rates are incredibly high.

Laura’s brother went to a one-month rehab, which cost her family twenty-one thousand dollars. They had some insurance, but still went about ten thousand dollars into debt attempting to ensure her brother’s recovery. Even though they were willing to pay for a more expensive rehab, they had to call several different facilities several times a day to secure him a spot in one. After he was finally admitted, paid the hefty fee and completed the program, he relapsed about three weeks out and is currently back to using regularly.

Syracuse addiction specialist, Dr. Laura Martin, said the methadone clinic in Syracuse has five hundred spots for treatment and a standard year-long waiting list. She has a loose-leaf notebook in her office with several pages filled with the names of opiate and heroin addicts who have come to her office looking for treatment and who she just doesn’t have room for. Pelow’s son has been on a waiting list for treatment since this past July.

In response to this national epidemic, many cities across the US are starting to implement social and community based responses to the rampant use of heroin, as traditional approaches continue to fail.

In Santa Fe, New Mexico, Emily Kaltenbach, the state director for the Drug Policy Alliance of New Mexico says she is tired of seeing the same nonviolent drug offenders filling the court’s dockets and burdening taxpayers with expensive jail stays. She is trying to implement a community-based social program to divert people away from jail before they are fingerprinted, booked and charged.

In Ithaca, New York, the mayor is proposing a safe place for addicts to get high but under the surveillance of health specialists. This would also be a step toward addicts getting serious help.

Ithaca and Santa Fe are just a couple examples of the alternative measures being taking by city and state government to compensate for the futility of federal policies.

However, there is an opinion increasing in popularity that even the Obama administration is tentatively on board with. This is the idea that heroin use should not be treated as a crime and addicts should not be framed as criminals, but heroin addiction it should be seen as a disease. Secretary of State John Kerry said in a statement recently, “We are seeing tremendous advances in our understanding of drug dependency and our ability to address substance use disorders as a public health — rather than a strictly criminal justice — challenge.”

The primary approach of prohibition and criminalization has merely fed the cycle of addiction over the years. When Pelow’s son went to jail, she said he gained access to more networks to feed his addiction. A criminal record also compounds feelings of hopelessness, as now beating addiction and starting life again becomes that much more difficult.

The criminalization of heroin use and the punishment associated with this disease also feeds into the shame and stigma around it. Pelow said for years she would hid the fact that her son was a heroin addict because she was embarrassed and afraid of being judged.

Historically speaking, heroin has always been a drug with the notorious reputation of being one of the most intense, expensive drugs for the long-term, hardcore drug addicts passed out in a back ally.

But this stigma is no longer relevant, according to data such as the 2001-2002 National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism survey, which shows that lifetime opiate users (including heroin) fall across a gamete of educational, age, and financial lines. Fifty-seven percent have attended college. Thirty-five percent make less than $35,000 in their annual salary. Thirty-nine percent are female, which stands out as unusual since studies show that many forms of addiction tend to disproportionally target men. But with opiate addiction, it is men and women, high school drop outs and college graduates, people driving Hondas and people with Ferraris. Today, opiate and heroin addiction does not discriminate.

But experts, such as Dr. Martin, say this image still connected with heroin is a force that inhibits users from seeking help and doctors from extending it.

“Most doctors don’t want to have a whole bunch of addicts sitting in their waiting room because they picture an addict as coming off the streets with a blanket around them and sleeping on their floor and that kind of thing. But really they come in suits and ties and from their college campuses,” Dr. Martin said.

And people that work with heroin addiction, like employees at ACR Health in Syracuse, say that this archaic stigma prevents addicts from reaching out and trying to get help.

Decriminalizing heroin would help in combating the stigma around heroin use and perhaps encourage more addicts to pursue recovery. This decriminalization would also mean families would not have to also contend with the myriad of legalities around arrests and criminal offenses and it could make a terrible situation incrementally more bearable.

*Laura Samson is a pseudonym. She was comfortable sharing her story, but not here real identity.

[1] The title to my article is straightforward and direct, but it communicates the seriousness of this issue and article. Since heroin use and the tragedies surrounding it are so dire and bleak, I did not want to be creatively or playful with the title. I wanted to retain a serious and level tone, which reflects the tone throughout the piece.

[2] I started the piece with an anecdote, which I heard first hand in my hometown of Oswego. It is a jarring and sad story that I thought would not only pull readers in (or ‘hook’ them), but also personalize a story that is a lot of big and scary numbers. The story of Amy Pelow and her son does not really provide initial background or rationale, but it is supposed to immediately make people feel and care. It does provide exigency, as the heroin epidemic is a timely and relevant issue and the fact the Pelow’s son is hospitalized in the beginning shows even more the urgency of this issue.

[3] I think I provide multiple ‘ideas’ in this article, each with analysis and supporting evidence. First, I discuss the extent of the epidemic and the factors that have created that situation. I use a variety of statistics and sources when constructing this section. Then I discuss the complexity of the stigma and resources and community-based responses and the need to decriminalize heroin. I struggled with flow and fluidly in this piece, but I thought I manage ‘ideas’ and their analysis well.

[4] As mentioned before, clarity and fluidity were issues I had in this piece because I had so much information I wanted to include to show the melee that is the heroin epidemic and how it impacts people and how the country is trying to respond. I thought my presentation and especially my anecdotes made my take of this issue unique, in addition to my final argument to decriminalize heroin use and why that is important.

[5] I think most of the arguments and information I provided was backed up and flushed out and not vague or cliché. When I stated something, I provided examples or quotes or data to prove it. For example, I discussed the impact of heroin addiction on family and loved ones and I used Laura as an example of that.

[6] I think I deeply researched this issue, but I do think my final argument of decriminalization could have been even stronger but I was not quite sure how to do that. But I covered many aspects of this issue, building a comprehensive stance and argument. I provide an overview of the epidemic and break down some of the complexities within this reality, like lack of resources or impact on family.

[7] I used a lot of sources and a diverse set of them from news articles to scholarly journals to academic essays to multiple primary sources.

[8] I think I meshed my sources into the article fairly well, but maybe I could have included them even more of them. I think I might have done the opposite of drop quoting. I researched this issue so much that I was confident to just write about it and probably could have referenced sources more.

[9] I think I could definitely persuade my audience that heroin use should be decriminalized. I tried to do this mostly through evoking emotion. I wanted to show readers how terrible this situation was for addicts and their families and how really it is not completely their faults for being there and grace and sympathy should be extended to them as opposed to judgement.

[10] I thought the first visual I used provided context for the increasing prevalence of heroin use in the US. I placed it is the beginning because it is one of the first aspects of this issue I address. I included the texts because I thought they might further evoke emotion from readers.

[11] My development was incremental. I started with too much information trying to include every aspect of this issue and slow edited some of that content out of the article.

[12] Yes, effective. But upon reflection, I think I probably could have included even more.

[13] I tried to use very powerful language and proofread several times so I think I used language effectively overall and presented myself as credible.